The effects of climate change are making life hard for the sensitive coffee plant. Experts warn that without appropriate countermeasures, more than half of the area currently used for growing coffee will no longer be suitable for that purpose. Katrin Simon from Erlangen Botanical Gardens, Julie Mildenberger from Weltladen Erlangen and Joelle Claußen from Fraunhofer IIS explain how phenotyping coffee plants, embracing experimentation and more conscious consumption can help ensure that coffee can remain a daily pleasure despite climate change and resource scarcity.

Tackling the coffee shortage with Fraunhofer technology and responsible behavior

27. March 2023 | Phenotyping coffee plants

Researchers predict that global warming will have such a profound effect on coffee growing that supply will no longer be able to keep pace with global demand. Could you explain more about this?

Katrin Simon: Climate change is a more accurate term than global warming. For a plant to flourish, it needs sunlight, rain and certain atmospheric and weather conditions. A change in climate spells trouble for the sensitive coffee plant. Changes in frost exposure, too much or too little precipitation, heavy rainfall and periods of drought all make life tougher for coffee plants and the people who grow them. In 2021, for instance, Brazil actually experienced frost severe enough to destroy a large part of the coffee harvest.

Julie Mildenberger: As a result of the situation in Brazil, the price of coffee has shot up by an average of 35 percent over the past year. A group of Swiss researchers estimate that by 2050, the total area viable for coffee cultivation worldwide will be less than half of what it is today. In fact in Brazil, some 97 percent of this precious land is under threat. But we don’t even have to look that far afield: farmers here in this region are also worried about drought and erratic rain patterns.

Speaking of this region, it is possible – perhaps with the help of technology – that coffee could be cultivated on a large scale in our part of the world?

Joelle Claußen: To grow the well-established varieties – arabica and robusta – here, the climate would have to change considerably. At the Development Center X-ray Technology, we’re investigating how plants respond when the climate is too hot or too dry, and when they are given too much or too little fertilizer. So I think that the focus should be on growing varieties of coffee that taste good and that can cope with changing climatic conditions.

Julie Mildenberger: Since coffee can’t tolerate frost, it’s definitely not a suitable crop for European latitudes. I’m skeptical in any case because coffee is essentially a luxury product, and agriculture’s main job is to feed people. Every piece of land devoted to coffee production would no longer be available to grow staple foodstuffs. As a crop exporter, Europe has more important things to focus on than coffee.

Katrin Simon: If coffee were to be cultivated here, it would be in hothouses. But that doesn’t make sense because of the energy footprint and heating costs. People have to accept that coffee is a finite resource, and it’s becoming a luxury item again. So everyone has to decide for themselves whether coffee is important enough to them to keep drinking it.

Are there coffee plants that can be cultivated to be resilient enough to flourish in the face of climate change?

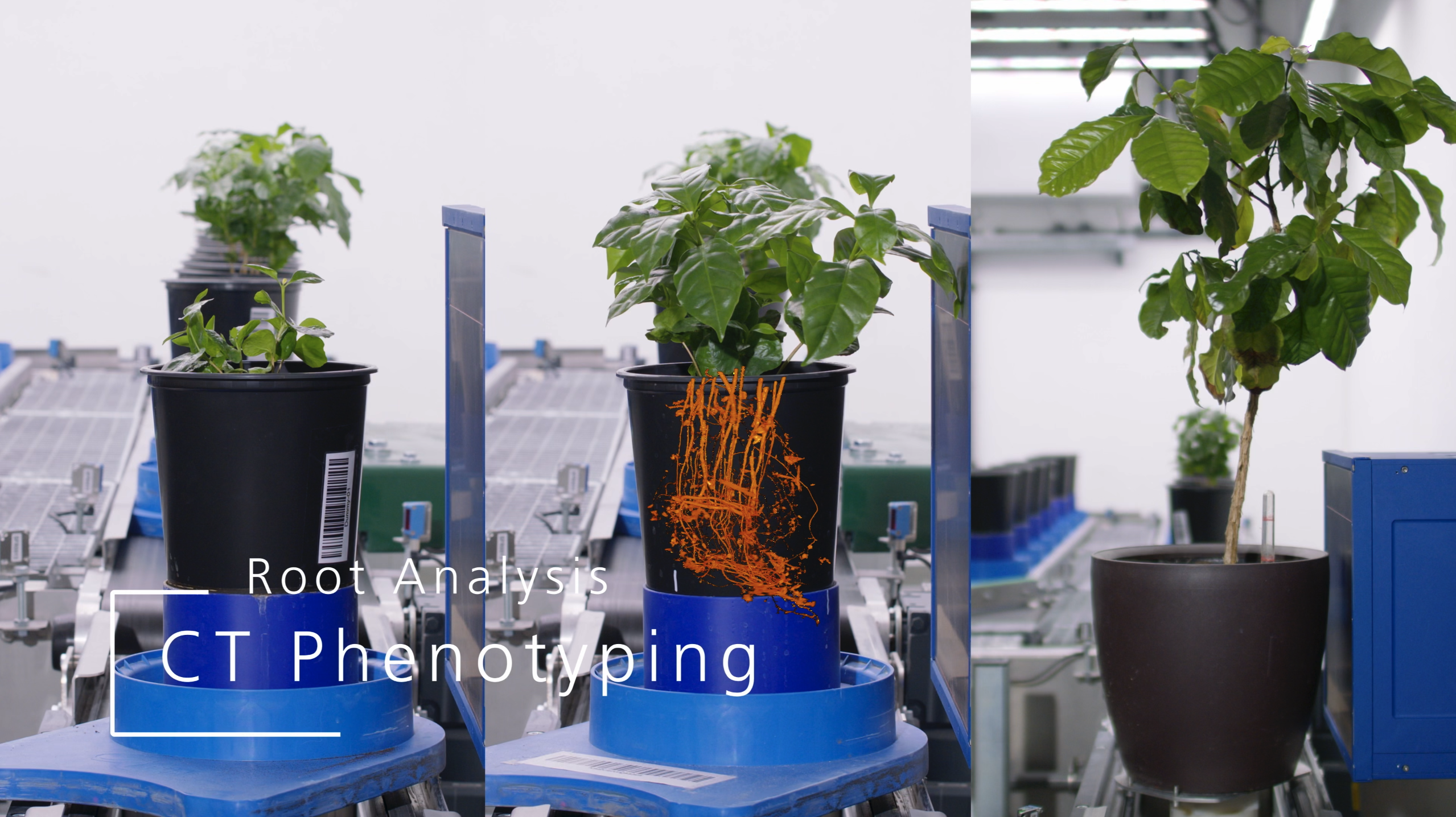

Joelle Claußen: To grow plants that are more resilient to environmental factors or pests, we first have to study them closely. When we’re phenotyping coffee plants, we’re systematically testing the work that the growers are doing: by applying optical methods aboveground and X-ray technology to look belowground, we can see how a plant grows and how it responds to environmental influences. Sensors allow us to objectify, simplify and accelerate tests that would be very costly and complicated to perform on several hectares of land.

Julie Mildenberger: It’d also be a good idea to align coffee cultivation to climate change. Indeed, coffee growers are already taking action: in Peru, some plantations have been relocated from 1200 to 1400 meters above sea level to offset the effects of climate change. We tend to romanticize the growing of coffee, but here it’s purely about survival. So I’m appealing to everyone to support these growers by buying fair trade coffee. Since smaller plantations can achieve a more delicate balance and experiment more, they quickly come up with new methods of cultivation. Obviously, the structures typical of small plantations are not the most economical. But they do have such a positive impact on both the landscape and our society.

Katrin Simon: Speaking of society, it’s important to know that robusta has a different taste to that of arabica, but that it is much more stable, resilient and thus easier to grow. After all, an imported cocktail tomato from a discount supermarket doesn’t taste the same as a locally grown organic tomato. The only way we can counteract climate change is to rethink the way we do things. The more types of coffee plant we cultivate and make available through open-source seed, the more coffee growing will be an effective countermeasure. The benefit of this diversification is that it will keep coffee from dying out in the future – it provides better protection against greater exposure to rain, drought and pests. And as responsible consumer citizens, we can all set new standards by being deliberate about what we buy and choosing products that carry certain quality seals. It’s our responsibility to embrace experimentation and to give robusta a chance.

What other options are there for addressing the looming coffee shortage?

Julie Mildenberger: Protecting the climate is impossible without fair prices. The focus needs to be on organic cultivation, which has an entirely different set of tools for helping the plants adapt to these new climate conditions. And the fact is that organic farming costs more – small farms can’t survive on what we’ve been prepared to pay for coffee up to now. Even though coffee prices have gone up, they’re still far too low to tally with the sheer amount of work involved and what these organic farming structures would actually need.

Joelle Claußen: A lot of research is currently being into coffee alternatives, such as lupine coffee, mushroom coffee and caffeinated cocoa. I think that breeding more resilient plants is a solid approach, one that should be part of a concerted effort to mitigate the effects of climate change. Maybe we can’t do much as individuals, but together we can do a great deal to save coffee and the places that grow it.

The last question is a more personal one: It’s been said that a coffee break recharges both mind and mood. Wise words or utter nonsense?

Julie Mildenberger: I might not need the coffee, but I certainly need the break. That’s what recharges my mind and mood. Whether I enjoy a coffee, a good cup of tea or an ice cream, what counts is rethinking and changing my routine every now and then. A common ritual used to be the cigarette break: a reason to get up, go outside and chat with people. But hardly anyone smokes anymore. I’m sure that coffee will eventually give way to another context for taking a break.

Katrin Simon: I totally agree that it’s the break that’s the salient point. I now drink just one cup of coffee a day; the rest of the time I drink herbal tea. Of course cutting back could be seen as a drastic step, but for me it was a viable option and I’m curious to see where this journey leads. In any case, I now appreciate coffee much more than I used to and I enjoy it differently as well. So I recommend the break, with or without the coffee.

Joelle Claußen: Where I work, we have a small break room where colleagues can go to drink a coffee, have a chat and even vent a little if they’re having a bad day. And a coffee break can be about the coffee, but I’m sure it’s also a lot about the ritual. Having a tea or some other drink would be okay, but coffee is the drink of choice for many people. So I’d say wise words because I for one am a big fan of coffee and the coffee break.